00:00:00: Introduction

00:02:34: The pressure tipping point

00:07:10: A pressure performance matrix…

00:08:58: … top right quadrant

00:09:54: Idea for action: high-pressure practice

00:13:02: … top left quadrant

00:14:41: Idea for action: moments that matter

00:15:54: A coach-yourself question

00:17:04: … bottom left quadrant

00:18:04: Idea for action: fix if fast

00:23:31: … bottom right quadrant

00:25:00: Idea for action: acknowledge, ask, adapt

00:31:53: Solo sportspeople work as a team

00:33:54: Final thoughts

Sarah Ellis: Hi, I’m Sarah.

Helen Tupper: And I’m Helen.

Sarah Ellis: And this is the Squiggly Careers podcast. Every week, we take a different topic to do with work and we talk about ideas and tools that we hope will help you, and they always help us, to navigate our Squiggly Careers with that bit more confidence and clarity.

Helen Tupper: And if it’s the first time you’ve listened to the podcast, you might not know about all the extra stuff that comes with this episode. So we have PodSheets, they’re one-page downloadable summaries about what we’re going to be talking about so that you can take some action; we have PodNotes, they’re sort of small swipable, shareable things that you can get on social; we have PodMail, which just puts everything together in one place for you; and we also have PodPlus, which is a conversation we have on Thursday mornings, it last 30 minutes, and it’s a great chance to connect with a liked-minded community of learners who all want to dive a bit deeper with their development.

All of this stuff is free because we want to help. We want to help people with their Squiggly Career, and that’s what we’re here to do. You can find the links for all of those things, because I know it sounds quite a lot, but it’s in the show notes, or just head to our website, amazingif.com, and on the podcast page you’ll be able to find everything there. And if you ever can’t, just email us; we’re helenandsarah@squigglycareers.com.

Sarah Ellis: And for those of you who do listen to the podcast regularly, often I think the topics give you a good insight into how Helen and I are feeling and what’s going on in our world and in our organisation at the moment. And this week, we’re talking about performing under pressure.

So, we’ve had quite a lot of high pressure moments in the last month or so, and we were reflecting on what helps you, what hinders you, the different types of pressure and how perhaps we’re better in some situations than we might be in others, and how we can learn the skill of coping under pressure; because I suspect as we go through today, everybody listening will be able to think of pretty recent, and also frequent, examples of where we have to cope under pressure. What I think we really want to help you with today, and clearly help ourselves with, is kind of moving from coping to feeling like we can perform.

And I think when we’re performing under pressure, it’s still hard, but we come away feeling proud of ourselves that we’ve made really good progress. I think if we feel like we’re coping, I always feel like, you know when you’re doing something by the skin of your teeth, you’re like, “Okay, I just made it through that moment [or] I just made it through that day”. And I think given all the change and uncertainty of Squiggly Careers, if we can get to performance more regularly, we’ll be doing a good job for ourselves.

Helen Tupper: And when we’ve been diving into, how do we perform under pressure, I think one of the interesting things that I found is that there’s sort of like a pressure tipping point. So, there is some evidence, actually quite a lot of evidence, that shows that some level of pressure can actually help your performance. There’s a really good article that we’ll link in the PodSheet from Dr Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, which talks a little bit about this point. And he picks out in his article the example of athletes who often will perform at their best on show day. I’m not really into sports, I don’t know what it’s called, but you know, the day that they’re at the — what’s it called, Sarah?

Sarah Ellis: I’m enjoying show day!

Helen Tupper: What is it called? You know, the event, the moment, that one.

Sarah Ellis: The competition?

Helen Tupper: Yeah, show day, very literal!

Sarah Ellis: I’m sure if you ask the people, the guys who played in the Ryder Cup over the weekend, and I think one of the examples you shared with me when we were preparing for the podcast was golf, I’m pretty sure they don’t describe the Ryder Cup as, “Oh yeah, it’s the show days”!

Helen Tupper: I mean, I think they should! The day of the big show, guys, I definitely envision! Anyway, the point is that on that day, whatever it’s called, you often get peak performance because the excitement, the sort of anticipation, the weight of that situation often creates a better performance. But there is this tipping point. And a tipping point is that when we are under pressure, our performance starts to slip when we become self-conscious. So when I might start thinking, “Oh gosh, am I doing this right? I’ve done this better before”, I start to internalise a lot of what’s happening.

That results in anxiety, “Oh, this is going to be a disaster”, so almost my internal monologue is sort of drowning out what’s happening outside of me. And we might be afraid of being judged. So, in those high-pressure situations, when our anxiety and fear of judgment and almost becoming more self-conscious starts to hijack our brain, that is when we lose performance as a result of pressure. And what that might look like is, you start making more mistakes, so errors, or if you’re presenting, you might miss words out, you might forget things. I found this really important actually in the research, that the part of our brain that stores facts and data is particularly vulnerable under pressure.

Sarah Ellis: Oh, interesting.

Helen Tupper: Yeah, that’s what I thought. If you’re doing a presentation and you start to worry about what other people think about you, one of the first things that’s sort of a threat is your ability to remember those facts that you want to, so it’s a double impact.

Sarah Ellis: Annoying.

Helen Tupper: I know, I was like, “That’s really annoying”, that’s the one thing I want to remember. Have a Post-it Note! But also, you might say and do things you didn’t mean to. I think this is quite interesting. When you’re under pressure, it might be like a flippant comment or just almost like an inappropriate joke. You know when people feel awkward and they just say things that they don’t mean to? It’s because it’s sort of hijacked your brain and you’re not as in control as you want to as a result of what’s going on.

Sarah Ellis: I suspect there’s also, as you were describing all of those different characteristics, it really reminds me of some of the work that we’ve done around confidence and self-belief, because I feel like these are the times where our confidence gremlins start shouting quite loudly like, I wonder what everyone’s thinking of you, or those people, they’re definitely judging you, they’re thinking you’re not good enough or smart enough.

That pressure tipping point, I suspect, is also really related to how much self-belief we have in that moment, because I think to perform under pressure and to cope with some of the scenarios that we’re going to describe, you’ve got to have that belief in yourself. If you’re already feeling low in terms of confidence, you imagine what this must do to people. And I suppose that’s why you sometimes also see, if you do look at those like high-profile examples of sporting people where it goes disastrously wrong, they’re an incredible player and then they completely lose it, and you just wonder if that’s like a combination of all these factors coming together.

Helen Tupper: Well yeah, there’s again in the PodSheet, because I have done a bit of research, which we’ll come back to in a moment, there’s a really good link to a short visual sort of TED talk, I think it’s like TED-Ed, it’s only a couple of minutes long, and it talks about the choke effect, which is always a funny word, isn’t it, but when people choke when they’re under pressure and why that happens. I say we’ll come back to the research that I’ve done because we’ve had a bit of a role-reversal for prepping for the podcast this week, in that I was like, “Oh, I’m going to dive in all over”. I’ve been very curious and watching some TED Talks over breakfast and reading some articles and I kind of dumped it all in a document to talk to Sarah about. She’s like, “Helen, I’ve made a matrix”, which is normally the exact opposite way that this happens when we are prepping for most things in our work together! So, Sarah, would you like to introduce people to the matrix that the rest of this episode is going to be structured on, so people can help feel more confidence in how they perform under pressure?

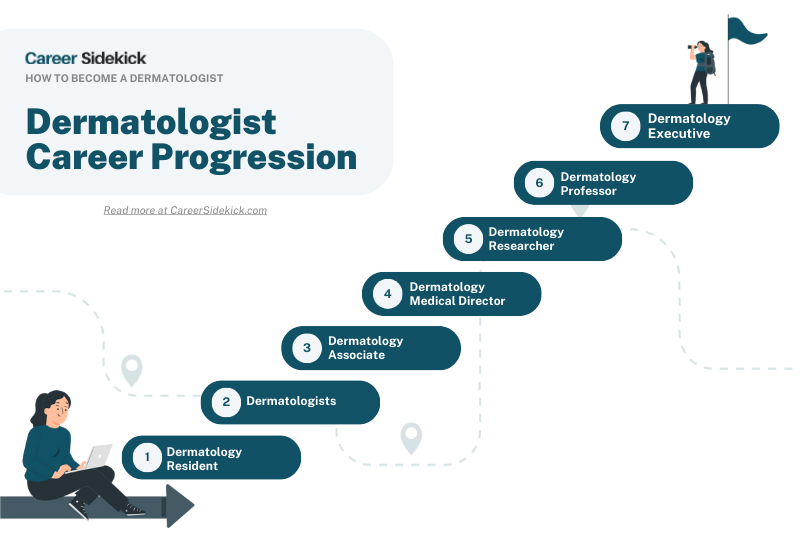

Sarah Ellis: Well, I think our observation here is that not all pressure situations are the same. So, what we’re trying to use the matrix for is to reflect some different scenarios, because we felt like the ideas for action will vary depending on each of these situations. So, here’s the matrix and hopefully I’ll do a decent job of describing something that’s quite visual while you’re all listening. Obviously it will be in the PodSheet as well, but hopefully it’ll still make sense. So, on one axis here you’ve got pressure and at one end of the spectrum you’ve got “anticipated pressure”, and at the other end you’ve got “unanticipated pressure”. So, sometimes we know it’s going to be a high-pressure situation, sometimes it takes us by surprise.

On the other side of the matrix we’ve got “amount of control”. So, sometimes we feel like we’ve got really high control in a situation, and in other examples you might feel like you’ve got really low control. So, for each of those quadrants and we will remind you what they are as we’re talking them through, we’re going to share an example or just a couple of examples to really try and bring these things to life, and also maybe help you reflect on which of the ones do you already do well, because Helen and I have realised actually in certain parts of the quadrant we’re both really good, and then in other parts of the quadrant we’re like, “Oh, but we find that one really hard”. So, I think this helps you to be more specific as well about where you’re already great and maybe the gaps you’ve got. Then we’ll talk about for each quadrant, an idea for action. So, if you know you’ve got that coming up or if you know that’s one that you find hard, what might you do differently? Or, with the ambition of it sort of equalling performing well under pressure.

Helen Tupper: So, where are we going first on this matrix?

Sarah Ellis: So, let’s start with the top, right-hand of the matrix, which is where you’ve got anticipated pressure, so you know it’s coming, and you’ve got high control. And so, for example, we were thinking about when does this happen for us? Probably our biggest example, or most significant example, was when we were doing a TED Talk. So, really high pressure moment, you want to get it right, you’re hoping lots of people are going to watch it, so it feels like loads of pressure. But you also have a fair bit of control. You get to write the TED Talk, you know what’s coming, it’s in your gift to make sure you practice and rehearse for it. So, high control and high pressure.

Helen Tupper: And so we appreciate that not everyone’s doing a TED Talk every day, so maybe some more frequent situations might be like a big presentation at work. You’ve got that moment in your diary, you know it’s coming, and like Sarah said, you can prepare for that, but it still feels like a high-pressure moment for you in terms of your work. So, the idea for action here is to do high-pressure practice. So, what you’re looking to do is to get as close to that situation as you can. So, you can practise, if it’s a presentation, for example, you can practise what you’re saying, maybe even in the room that you’re saying it to. Because I’ve had this before, where if it’s the first time you’re in that room, sometimes that can also take your control away, because you’re like, “Oh, I didn’t know it was going to look like this, I didn’t know it was going to work like this”.

But if you can go and do a recce of a room, you can often feel more control in that situation. Maybe what you could do is you could record your presentation. That’s what we did with our TED Talk. We couldn’t get into the room, so what we did do as a bit of high-pressure practice is we recorded our presentation on Zoom and we sent it to somebody, our lovely friend Bruce Daisley, who we mention a lot, so that we could get feedback; and not just Bruce, a couple of other people too, so that we could get some feedback. And it felt like quite high-pressure practice, because we weren’t that confident and we could have just done it on the day. We could have just done it on the day and probably been a bit ignorant of what other people thought. But the fact that we had created it and sent it out and got people’s feedback meant that on the actual day, we felt much more confident about what we were communicating, because we’d done that bit of work beforehand. And it’s really important. You’re basically trying to keep your control in that moment, because the moment that you feel like you lose control is the moment that your performance will fail at that point under pressure. I think this is the one, Sarah does this really well.

So, Sarah will often look ahead in her diary. I think you look at like, what are those moments of potential high pressure, so that’s your anticipation, and then you prepare for them really, really well. You’ll flag it to me, you’ll be like, “We need to talk about this [or] I’ve done this”, whereas I think for me, because I’m a bit more in the moment, I don’t think I do the anticipation so well. I think that’s the bit I lose.

Sarah Ellis: Yeah. I think my natural tendency to look ahead, I’m good at forward thinking, I’m a visualiser, I imagine the situation and then I think I bring it back to a so what. So, if for example we’re going to be talking to 300 people, “What do we need to make sure that we get right? Okay, we need to make sure we know what I’m going to say versus what you’re going to say. We need to think about is there anything we need to adapt? We need to think about how we’re going to respond with things like questions”. So, I think I do quite a lot of imagining which really helps me with high pressure practice, and I’m good at sort of forcing myself to get as close to the kind of reality that I know is coming as possible, because I see that I’m just better because of it. So, I think this is the one where I feel most confident in my capability to perform under pressure. That reduces a little bit as we walk through the quadrant!

Helen Tupper: Just your point there on visualisation, in that extensive research that I did, that did also come up as a really important point to cope with pressure, is to sort of visualise a positive outcome. You don’t want to do that on its own, but I think practice and that kind of, what does a positive outcome look like, and kind of holding that in your head work really well together, just as Sarah described it.

Sarah Ellis: So, now we’re going to move across the matrix. So, we are still in an anticipated high-pressure moment. So, again, you still know it’s coming, but you’ve got low levels of control now. And so Helen and I were thinking, this might be one that feels very frequent for all of us. You know when you’re looking ahead to your week and you are thinking, “Wow, that is a lot”, and a lot of it feels like it matters. So, you’re perhaps feeling like there’s a lot of overwhelm, there’s almost too many things all happening, but you can’t change those things for now. Maybe there’s just a lot of meetings, a lot of projects, a lot of things all happening at exactly the same time, and you don’t have that ability to just say, “I’m just going to stop these things [or] these things can just wait”. Helen and I often describe these as crunchy moments. I think we just always go, “Oh, it feels really crunchy”. I don’t know why that just ends up being the word that works for us, but again, we anticipate those. You can look in your diary and you’re like, “Oh, it’s a crunchy week”, or sometimes maybe it goes beyond that, “It’s a crunchy month”. And so again, you want to be thinking about, well, rather than just being like, “How do I cope with the crunchiness?” you’re actually, “How can I still perform? How can I still be at my best in this anticipated high-pressure, but low-control moment?”

Helen Tupper: I have frequently said to people in the last week or so, “The next eight weeks are going to be really crunchy”. It’s not a moment, it’s a series of months, because I can look ahead! This one I am better at looking ahead at, but what I still don’t think I do very well is kind of prepare for them so that I can perform under pressure, which is where this idea for action comes in. So, the idea for action here is to look at that period of time that you might consider crunchy, or whatever your language for it is, and think about what moments really matter. So, what do you want to be absolutely great at in that day, in that week, in that month; what are the moments that really matter; and which moments are okay to be good enough? I think the trap that I get in is, I look at those eight weeks and I think it’s all got to be brilliant, and then I just try and put more and more hours in and more and more effort in, and I beat myself even more when I make mistakes, and that compounds, etc.

Not helpful, definitely my performance drops over time. Whereas actually, what would be much more helpful is if I look ahead for that period, and then I pick out a moment a day, a moment a week, whatever it is, that I’m going to make great, and I go after that particular moment. And the rest of it, you’re like, “Well, what would good enough look like?” because it’s really hard to make anything great if you’re trying to be brilliant at everything. And I think we’re trying to acknowledge that sometimes it’s okay to be good enough at stuff, and we have done a podcast on this. So, I think if you struggle at that, I think maybe the podcast that we’ve done on when it’s great to be good enough is a good listen after this one today.

Sarah Ellis: So, a sort of coach-yourself question here that Helen and I were both reflecting on that we find really useful is, “Where does it matter most for me to perform under pressure this week?” Use whichever time frame works for you. But you are very consciously picking out, and you can do it because you can anticipate it, you’re like, “This is the moment where I do really want to be at my best. And actually, do you know what? I can almost consciously get through the rest of it”, and sometimes I think that is what it is. You’re like, “Okay, well, I’m going to turn up and contribute and do the best I can”, I’m very consciously choosing, which actually when you’re in low control moments, having some conscious choice helps you to regain a bit of control. So, you’ll also probably feel better just by doing that, and then you’re more likely to perform better as well.

Helen Tupper: And I think you just don’t beat yourself up as much. Like, if I look at this week, and we had this chat, we were like, “What’s that point that we want to perform our best under pressure this week?” and we both had the same point, and suddenly you go, “Well, it’s not that I’m going to be bad at the other stuff, it’s just that I’m not going to maybe obsess over it quite as much, I’m not going to go all those different details, and that’s okay”.

Sarah Ellis: And so now we move to the next bit of the quadrant, which is my least favourite of the four, which is where you’ve got low control and it’s unanticipated pressure. And I just think, low control, no thank you; unanticipated pressure, no thank you again.

Helen Tupper: I quite like this. This is my favourite one.

Sarah Ellis: I know you do. So, you can talk about this, and then I’ll talk about why I really dislike this quadrant so much.

Helen Tupper: So, a situation that maybe this might feel familiar to you, where you feel like you’ve not got a lot of control and this is unanticipated, maybe you’re in a meeting; tech is our one that Sarah and I always talk about with this one. So, you’re in a meeting, you’re in a moment, you’re about to present, and then your tech just fails and you just can’t seem to fix it. You’re like, “I’m not the person who’s experienced in how all these plugs and wires and whatnot go in”. And it’s because it’s unanticipated and you haven’t got control because you’ve not necessarily got experience, it can feel really, really daunting. And you can get a bit flappy I think in these types of situations. And the idea for action here is to fix it fast, and what we mean by that is we’re kind of recognising that this didn’t go the way we want it to, and what we’re trying not to do is for everyone to see us flapping, so we’re trying to take some control of the situation. So, I’ll give you an example of a situation that I’ve been in recently where my tech failed. Flapping would have been me trying to fix it in front of everybody.

But what I would tend to do is if I’m doing it virtually, I would tend to say, “Can you just give me two minutes to fix my tech?” and I would take my camera off so people aren’t seeing me restarting things and putting in plugs and trying to get cables out of bags, because they don’t necessarily need to see me flapping. What is important is that I can focus on that moment and fix it fast. What’s also important I think is that once you’ve fixed it, you want to get back on track as quickly as you can, and then I would always do a follow-up. So, I would always be like, “I’m really sorry for that situation” and then I’d kind of come back. So, I probably wouldn’t ignore that it’s happened, because people probably haven’t seen it and even if they haven’t seen it, that’s going to go around my head, I’m going to worry about it. And back to that point right at the start, we underperform under pressure when we become self-conscious and anxious. And so, I think part of the follow-up is that you close that story off and you go, “I’m really sorry that happened. I hope everything was okay after that point.

Let me know if you’ve got any feedback”. That’s me regaining control rather than letting this worry sit in my head. So, at any moment when you’re like, “I didn’t think this was going to happen and I don’t know how to sort it out now”, so unanticipated low control, just think about, “What does fixing it fast look like for me right now, but I don’t want people to see me flapping, so how can I create a bit of time so I can sort this out?” and then do a fast follow-up, so you still feel in control of it. I quite like these, because I quite like that unexpected pressure point, I quite like responding to it quickly. Sarah, I’d say less so, is that fair; is that a fair, less so?

Sarah Ellis: Yeah, I think this is one though where I actually feel proud of myself, because my inclination in this quadrant is not to fix it fast, it’s to run away fast. So, we were actually having a conversation before about, does your thinker versus doer preference impact your ability to perform under pressure? And our hypothesis is it probably does, in terms of your tendency to naturally do well in one of these quadrants versus have to work much harder in another. And so I’m a thinker, and I think low control and anticipated pressure, the problem is my thinking kicks in. So, all of those things that Helen was describing around, I sort of spiral. So, I had this happen last week, and I don’t think she’ll mind me saying because she saw it happen and she was very lovely about it.

So, I was doing a podcast interview with Amy Edmondson, coming soon, and the Zoom was working fine, and we were having a conversation until it didn’t, and it just stopped working. And all I want to do is run away and hide, and I want to stop the conversation, I think I’m thinking, “Oh, she must think we’re so unprofessional. And she’s probably judging us and being like, ‘Well, how can she not get this right? They do this all the time’”. So, I go into very, very quick runaway and spiralling, and my thoughts really dominate what’s going on in that moment. I think what’s actually been really helpful for me, and this is actually a good top tip for anybody listening to this, is spending some time with someone who’s good at the quadrant that you’re not. And because I’ve spent so much time with Helen, I have seen live, quite frequently, Helen fixing it fast and following up fast, and I’ve seen how effective it is. It is better than running away fast.

And so in those moments, I really sort of channel, because we’ve all got that ability to be agile, we’ve talked about that in the podcast, I just go, “Right, my job here is to try and fix it fast”. So actually, I was so proud when I was talking to Amy, it stopped working. We emailed her straight away and said, to Helen’s point, “Hi, Amy, sorry for the technical issues, can you give us ten minutes, can you come back in ten minutes, we hope we’re going to be able to fix it by then?” and also reassured her, “We won’t take up more of your time. And do you know what, my heart was going very fast for those ten minutes as my computer was reloading and I was like, “Oh my God, is it going to work?” But I stuck with it and I stayed in the moment and we did fix it, and it’s so much better to try and do it there and then, rather than come back to it or delay it in the hope it’ll sort itself out. And so I’ve just really trained myself to stay in the moment. Intuitively it is the exact opposite of everything I want to do. So, I was trying to think here, “Why do I feel so much better at this than I used to be?” And I honestly think it’s because we learn when you see different behaviours to your own role modelled, and I actually think it’s really helpful that Helen and I are very opposite here, because I might not be, well, I’m not, I’m not as good as Helen in these situations, but I am so much better than I was.

Helen Tupper: I’m thinking whether it’s also like exposure therapy! You know they say, the more you expose yourself to these situations, the more they just sort of normalise a little bit. So, now that you’ve been in them a few times, you’re like, “Yeah, I actually can cope with this”. But for the first time, yeah, just always have the fix-it-fast kind of thing in mind. That’s your priority in that moment if you want to perform under pressure. It’s not the right thing to always do, but in that situation, unanticipated low control, fixing it fast will help you through the moment.

Sarah Ellis: And the last part of our quadrant is when you’ve got high control but unanticipated pressure. So, I was describing this to Helen as, this is where things are going swimmingly and then there’s a side swipe that you just weren’t ready for. So, I don’t love this one either, to be honest. I don’t like unanticipated things. And so, this might be a person. So, maybe you’re presenting and someone says, “I disagree with you [or] I disagree with that”. Or maybe you just get put on the spot with a question that you don’t know the answer to. So, there’s something here that is trying to take away your control that you just you hadn’t anticipated it was coming.

Helen Tupper: And I think in this situation, where this was sort of your moment, this was your meeting, this is your presentation, it’s your project, this is like —

Sarah Ellis: How dare you?!

Helen Tupper: — how dare you? I know! But that’s where I think the default reaction to this, because of the pressure that you’re under, I think could be to attack. So, let’s say I’m presenting and Sarah says, “Well, Helen, to be honest, I disagree with that point”, in front of the team. I’d be like, “Well, I don’t think that’s appropriate, Sarah, right now”. I could kind of go on the attack and be like, “Let’s just take that offline, Sarah. This is not the time to talk about that”, because I am sort of trying to take back control in quite an ineffective way because the pressure is making me react. And that’s not really the most helpful thing to do in that situation. So, we think what we want you to do is stay in control, but what we don’t want you to do is have your emotions take control of you. A better way to respond to those situations is to, first of all, acknowledge; acknowledge what is happening. Now that might be, you might just need to take stock of a situation, go, “Okay, what’s actually going on right now?”

Or you might want to acknowledge what somebody is doing. So, let’s say, Sarah, we’re in a meeting, it’s a high-pressure meeting, Sarah’s doing something, I don’t know, she always does, but it’s something. So, I’m going to acknowledge it, and I’m going to go, “Okay, I really appreciate your perspective on that point”, so we’re not ignoring it, we don’t want to ignore it, we don’t want to avoid it, we don’t want to attack it, that’s not going to help. So, the first thing we do is we acknowledge. Second thing that we do is about asking. And a really useful thing to do here is to ask for support. So, you can sometimes feel quite isolated in those situations. So, let’s say we’re in a meeting and Sarah asked me a difficult question and I’m like, “Oh, I’ve got to answer it right now”, and it’s putting me under an awful lot of pressure. What I can do to regain control in that situation, I’ve already acknowledged her perspective. What I could do then is ask the people that might be in that meeting with me, “Okay, what’s your perspective on this [or] what are your thoughts on this situation [or] does anyone have an alternative view?” I am not trying to be the person who knows everything, the person who needs to answer every question. In fact, I’ve kind of got more control if that is not what I’m doing. If I’m the person who’s bringing in other people’s perspectives, if I’m the person who’s creating clarity, that still means I have control. So, we’ve acknowledged it, we’ve asked and then the next thing we might need to do is adapt.

So, maybe I might say, “Okay, Sarah, it’s really just a perspective. It does seem that other people have a similar kind of thought on this situation to you. Why don’t we take the meeting down that particular point right now, because that feels like it might be the most effective thing for everybody”. I am still in control of that situation by acknowledging, asking and adapting. Even though what we might now be talking about is not what I’d started with, the fact that I’m still in control of that conversation is the thing that kind of helps us to perform under pressure. If we just keep doing what we tried to do, even though other people might disagree with how we’re doing it, then we might start to look a bit defensive, it might not be very effective, it might not look to the people that we’re really in control of the situation or were listening; but if you can acknowledge, ask and adapt, you still retain control.

Sarah Ellis: I think this is quite a sophisticated skill, particularly where power dynamics are at play. Because I think for a lot of people listening, and certainly this really feels relevant to me, if you’re in a meeting where you’ve got more senior people, it’s often more senior people who might put you on the spot or maybe start to derail meeting, let’s be honest, that often does happen. And in those moments I think it’s really easy to feel like, “Oh, but they’re more important than me”, or I have to listen to them, and the powerful people in the room end up taking the control from you. But I think those people often really admire that ability to adapt, but while still kind of sensing that level of going, “But they are still in control of this meeting. It’s still Sarah’s meeting, it’s not suddenly become Helen’s meeting”. Also, if somebody is naturally a bit destructive, actually again doing that acknowledge, ask, adapt might mean that you say, “Okay, well today, as we’ve got everybody here together, I still think it’s useful for us to talk about… but actually maybe you and I have a conversation about this”, so again, you’re not ignoring the person. I think this one does take practice, it can feel hard, and the first word I wrote down in this quadrant was “support”.

I think you can feel quite alone in this quadrant, in this situation, and then you stop performing under pressure. And then you feel so frustrated afterwards because you think, “Well, I knew the answer to that. I know I can be better than that”. This is one where, if you can just give yourself a moment to think or just a tiny bit of time to recover because you hadn’t anticipated it. So, it’s really easy for you to, as Helen said, withdraw, defensive, attack, all things that are not you performing under pressure, just some sort of small tactics here I think that just sort of keep you focused, help you to just regain back a bit of control, but letting go of what you had originally planned doesn’t necessarily mean performing under pressure. Actually, adapting and really listening might be incredible performance under pressure, and I think that’s often really true. I think that’s what people are sometimes looking for, that ability to understand, as Helen described there, “Actually, do you know what? There is something more important for us to talk about today”. And you almost acknowledging that and then going, “So, let’s use our time today to do that because that feels useful”, that’s incredible. That’s such a good thing to practise doing. Again, if you’re like me, I think the reason I sometimes find that one hard is I’m like, “Oh, but I’ve got a plan. I’ve got five more slides to talk through. Just letting go of that being a positive outcome, much more of a positive outcome, if you have a really productive discussion where you’ve created loads of clarity, as Helen described, and you’ve got a very clear way forward, that’s more important than the six PowerPoint slides that you were hoping to talk through.

Helen Tupper: So, I guess the main message that we’re trying to get across with the episode today is we want to move away from this idea that we just have to cope with pressure. Pressure is pretty normal in the work that we’re doing because all the things that we’re trying to do, but just coping with it is not necessarily that confident or healthy a response. What we want you to be able to do is to perform under pressure and we need to recognise that different things contribute to pressure situations, so anticipated or unanticipated, low control or high control. But if you can almost start to assess those situations that you’re in, in terms of where they might sit on that matrix and then respond to it whether that is with high-pressure practice or just thinking about what do I need to get great at, what’s good enough, fixing it fast or the acknowledge, ask and adapt, then matching that response to the high-pressure situation will give you the confidence, it will give you the control and most importantly, it will allow you to perform under pressure, which is what we all we all want to be able to do at work.

Sarah Ellis: So, good luck, we really hope it helps you. There’s also moments, right, like we’ve had quite a lot of these high-pressure moments over the last few weeks, you just think, “I could just do with a few days without them”. That is also okay, where you’re like, “I’d like to not have to perform under pressure just for a bit”. But we know it’s going to come our way, whether it’s anticipated or unanticipated, whether we have high or low control. And so I think the sooner we have these ideas, tools, and tactics, and as I described, even when we find them hard, exactly like I do, certainly with those bottom bits of the quadrant, I just then think we’re more prepared for them and we can just be more at our best and make sure that we don’t then lose confidence and we don’t show all the amazing strengths and skills that we’ve got to give.

Helen Tupper: Maybe just one extra thing, I was just thinking there, that we talked about this in the podcast about it being very individual, like when “I” am in a high pressure moment.

Sarah Ellis: That’s true.

Helen Tupper: But what really helps me is a lot of these moments are shared moments and the language is really important. So, I might say to Sarah, “Look, Sarah, this is just a situation where we need to fix it fast”. Or we might say, “Why don’t we do a bit of high-pressure practice so that we know we’re ready for it?” So, I think also the “we” element of this is important because you can talk about it more as a team, and that’s when I think the language really matters, because the more familiar these terms are, like what do we need to get great at and good enough, all the things that we’ve said, I think the easier it is for teams to talk about. So, this potentially could be a really good topic to talk about within your team, like take the PodSheet, talk about it in a team meeting and see how you can support each other with this skill too.

Sarah Ellis: Yeah, and it is interesting actually, building on that, how even when you hear, back to where we started, which incredibly for you was about sport, even when you hear people who play very individual sports, tennis is quite individual, certainly singles, golf is very individual, potentially, well, there’s one person with one golf club, whenever they talk on TV about how they’ve done and how they feel like they’ve performed under pressure, they never use I, they always use we. And I’ve talked to Helen about this before, and I find that really interesting. They’re in a very individual sporting context, but the reason they use we is because there’s lots of people that contribute to their ability to perform under pressure. So, even in those contexts where you might be like, “Oh, surely that’s all about how that individual does”, they’re always talking about team. So, I think that’s actually a really important point there to kind of go, “What does this look like for us collectively?” as well as probably reflecting on for you, when are you at your best, because then actually you can work out, “Well, how can I help other people?” Helen has helped me to get better at fixing it fast, I’ve helped Helen with high-pressure practice, and I suspect most teams have a kind of mixed profile. So, again, just that point about learning by osmosis and from each other.

Helen Tupper: I love it. Well, thank you so much for listening today. As we said right at the start, you can find all the resources, particularly the PodSheet, which I think will be really useful for this episode because the matrix will be there, which will kind of bring to life what we’ve talked about today, on our website at amazingif.com and you can link to that through the show notes if you listen on Apple too.

Sarah Ellis: But that’s everything for this week. Thank you as always for listening, and we’re back with you again soon. Bye for now.